5. Between tradition and modernism

One pair of garden pictures, in particular, seems strikingly modern. This is not simply because the two girls in the frame have been pictured from above – almost certainly from a window – but also because they stand out against the snow as undefined dark shapes [1-2]. In photographs such as these Breitner can be seen as a modernist or certainly a proto-modernist. In his time the use of such viewing angles was derided and dismissed as unnatural by professional photographers and critics. The world of Dutch photography was not known for a particularly progressive attitude; rather it was recognised as extremely conservative with an insistence on following the traditional aesthetic rules of painting, which was considered to be a much higher art form. The photographs in which Breitner adopted an unusually high or low viewpoint, stood very close to his motif, allowed movement to blur, showed figures out of focus

[3-4], partially truncated or thrown into the margins [5] – these were new-fangled devices for which contemporary experts on photography had no respect [6-7].

1

George Hendrik Breitner

Twee vrouwen in de sneeuw

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 80

2

George Hendrik Breitner

Twee vrouwen in de sneeuw

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 83

3

George Hendrik Breitner

Gezicht op de Prinseneilandsgracht te Amsterdam

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 218

4

George Hendrik Breitner

Twee passanten

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 78

This may partly explain why Breitner did not wish to be known as a photographer and shared his interest only with a small circle of close friends. He kept apart from the ‘photographers’ clique’. This was not just because he was a painter rather than a photographer by profession, but also because he feared that a reliance might be held against him on mechanical images (which is how photographs were regarded at the time), and because there was no aesthetic connection between his work and that of established photographers.1 There was no reason why he should join any photographic society or take part in exhibitions or competitions, or put forward his views in one of the journals of photography.

Only one letter (undated and addressed to Van Wisselingh, his art dealer) has survived in which Breitner wrote openly about the relationship between his paintings and his photography; only once (1903) was he on the jury of a photographic exhibition, and on only one occasion (1908) is he known to have helped in the selection of photographs for exhibition.2 The rest of the time Breitner stayed silent about his interest in and use of photography. Few people would have understood or appreciated his style and choice of subject matter. His approach was more rough and ready, less polished than that of other photographers in Amsterdam and the rest of Holland (and it should be noted that even abroad there were few active ‘kindred spirits’ besides his painter colleagues Bonnard, Denis, Munch, Rivière, Vuillard and Zille). In Breitner’s work we can see a preference for humble subjects – horses, servants, workmen – which are rarely seen in the work of other photographers (whether professionals or serious amateurs). Those who did treat these subjects usually did so in a sentimental and/or picturesque manner.3 This is a far cry from what Breitner did. Though no one realised at the time, the approach he adopted meant he was ‘ahead of his time’ and gave him a unique position.

Breitner did not resort to soft-focus or other tricks of the trade that were popular and widely used in photography. Instead, he was an early practitioner of the snapshot: the raw, unpolished image created with a complete disregard for conventional rules of composition. As we saw above, the term ‘snapshot’ was often used for pictures made with no sense of composition, no artistic pretension or technical skill, resulting in all kinds of ‘formal errors’ such as poor focus, exaggerated foreground, sloping horizon, and under or overexposure [8]. In about 1900 the majority of snapshots were made purely for pleasure by men and women pointing the camera at family and friends. Their main aim was to preserve a memory. Serious practitioners of photography had nothing but disdain for such snapshots and could only reluctantly accept their existence.

5

George Hendrik Breitner

Soldiers during a military march, voor 1915

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 1850

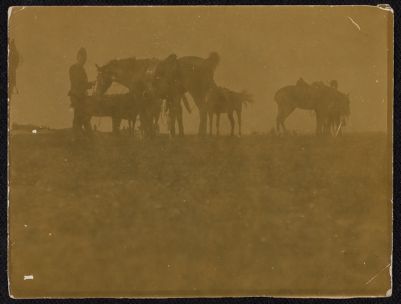

6

George Hendrik Breitner

Man and horses on the snow (newly built area at the Overtoom in Amsterdam), 1900-1905

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 2194

7

George Hendrik Breitner

Soldiers with horses during a military exercise

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 2206

Many of Breitner’s negatives and prints are technically far from perfect. They suffer from a lack of contrast (resulting in pictures that are generally grey) as well as too little light, so that areas become so dark as to be undefined, and it is difficult to make out any detail. His imperfect technique and avoidance of conventional compositional rules are both typical features of the snapshot.

There is one aspect of Breitner’s photographs, however, which distinguishes them, and those of other painter-photographers, from ordinary snapshots made by amateurs with no artistic background. We cannot attribute to a painter such as Breitner a failure to understand composition. Even if he had no specific artistic aim in making photographs beyond using them as preparatory studies for paintings, and so was not using photography as an art form, it was always the eye of a painter that was looking through the camera. For all the differences than can be detected between his paintings and photographs, the similarities are abundant and unmistakable.4 In both, the main aim is to register quick impressions of bustling street life. Even if he did not set out to make untidy compositions that suggest more movement and liveliness than static, carefully planned compositions, he must in any case have known that he was ‘sinning’ against the prevailing aesthetic norms.

8

Willem Frederik Piek

Pisa, Duomo en campanile (leaning tower), 1889-1893

Lichtdruk, 8,7 cm ø

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. nr. RP-F-F01198-EG

Breitner’s avoidance of the traditional aesthetic cannot be explained by a lack of visual sense; nor should we assume that the imperfections of his photographs are purely a matter of technical incompetence, carelessness or indifference. It was noted above that several of Breitner’s photographs were underexposed, producing large areas with little or no definition. One cannot help thinking, however, that this is a stylistic device he used consciously. It might be concluded from surviving negatives and prints that Breitner was careless and simply incompetent when it came to exposing and printing his negatives, but it is quite possible that he purposefully ‘played’ with technique. The way in which he lets the dark shapes of figures stand out as silhouettes against a pale background, instead of exposing them ‘correctly’, seems deliberate.

9

George Hendrik Breitner

Baan te Rotterdam, 1906-1907

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 435

10

George Hendrik Breitner

Gezicht op de Schiedamsedijk en de hoek met de Leuvebrugsteeg, after 1906

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 1323

Breitner more than once chose an unusually high or low viewpoint to make his subject stand out from the background. Besides the photographs of the two girls in a snow-covered garden mentioned above [1-2], there are plenty of other examples including photographs of military manoeuvres which he must have taken lying flat on the heath [7]. Had he been standing upright in the garden or on the heath, holding the camera at normal eye or chest height, the two girls would have been much less sharply defined against the fence or foliage (or whatever is bordering the garden) and the horsemen would scarcely have stood out against the heath. He created this kind of sharp contrast not only by choosing a low or high viewpoint, but also by taking photographs with contre-jour or sharply raking light [9-10].

It is clear from two small-format prints depicting a military manoeuvre and based on the same negative [11-12] that Breitner understood the effects of photographing against the light and enjoyed the contrast of silhouettes against a pale background. In the first picture everything can be distinguished clearly though the contrast is generally slight; the second print, on the other hand, is underexposed so that the dark areas hold very little detail. Breitner probably preferred the second image, since many of his photographs of cavalry manoeuvres show the soldiers, horses, carts and canons as black silhouettes [13-14]. The strong contrast between light and shade produced by underexposure and contre-jour give these photographs a dramatic quality that was highly unusual in Breitner’s time.

11

George Hendrik Breitner

View of three horse-riding militars during a military exercise, 1889-1915

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 2172

12

George Hendrik Breitner

View of three horse-riding militars during a military exercise, 1889-1915

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 2171

13

George Hendrik Breitner

Groep militairen op paarden tijdens een militaire manoeuvre, c. 1892

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 1543

14

George Hendrik Breitner

Twee militairen te paard tijdens een militaire manoeuvre, c. 1892

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 1548

Possibly the most important indication that Breitner deliberately worked with contre-jour lighting and contrasts comes from one of the small paper envelopes in which he originally kept his negatives and on which he noted the subject or motif. These envelopes must have been included in the gift that was presented to the RKD in 1961. Some of the labels, in Breitner’s handwriting, are purely topographical, naming streets such as ‘Kalverstraat’, ‘Spui’, ‘Overtoom’; others refer to particular motifs, for example ‘Horses seen from the side’ or ‘Horse and wagon’. On one of these small envelopes Breitner wrote: ‘Horses against the light’. Clearly he intended to group together negatives (we do not know how many) in this very envelope; we can only conclude from this that Breitner had a specific interest in the effect of contre-jour. Besides horses, he also photographed parts of the city against the light. In one view of the Prinsengracht he has underexposed the image so that the mast of a boat, the tower of the Westerkerk and a lamppost form a beautiful line-up of silhouettes [15]. Rainy weather would intensify the effect of contrast created by contre-jour. Then the sunlight would appear reflected from the cobblestones and they would stand out more strongly against other areas of the image that were in shadow.

15

George Hendrik Breitner

View on the Prinsengracht in Amsterdam, 1889-1915

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 2185

Breitner exposed and printed his negatives in a way that was unfamiliar to his contemporaries (and would have only been scorned by them) and this shows us that he was experimenting with technical possibilities.5 It is particularly his use of silhouette that makes his work seem modern.6

But of course not all of Breitner’s photographs are modern in feel. Besides photographs with high and low viewpoints, close-ups, blurring due to movement, silhouettes and unbalanced compositions, there are many images which appear more considered. Among the 13 x 18 negatives, in particular, which were made with a large camera on a tripod, there are many that give a completely different impression of Amsterdam. The city seems to be submerged in a Sunday morning mood. The streets are almost empty, and there are no people who wander accidentally into the frame. These large-format compositions are also much more peaceful and harmonious.7

Most of Breitner’s photographs were taken with small cameras which allowed him to work quickly and easily. Although he is modern in his use of the snapshot and through being one of the first to set out to record street life, Breitner also had another, more conservative side. The city of Amsterdam changed dramatically in the period after he moved there in 1886, yet we see very little of these developments represented in his photographs. The great new building projects such as Central Station (completed in 1889) and Berlage’s Stock Exchange (1903) make only rare appearances, and even then in the background [16]. Various large buildings went up in the second half of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century which had such a distinctive presence that it must have been a deliberate choice by Breitner not to picture them: the Volksvlijt Palace (completed 1864), Amstel Hotel (1867), The Nederlandsche Bank (Dutch National Bank, 1869), the Rijksmuseum (1885), Carré Theatre (1887), Stedelijk Museum (1894), City Theatre (again 1894) and the Bijenkorf department store (1914). Breitner restricted himself to the intimate ‘old city’. He certainly enjoyed photographing building sites, but only so long as the piles were being driven in and workers and horses were still working in the sand and mud [17]. As soon as the foundations were complete and the building proper began, Breitner disappeared. Furthermore, although he was very interested in horses and horse trams, he was clearly less enchanted with the electric trams that appeared in 1900, calling them ‘ugly, soulless boxes’.8

Breitner’s birthplace, Rotterdam, was possibly changing and modernising even more rapidly, but here too he looked away from the new developments. It was only the Rotterdam of his childhood, especially the old centre, that he captured in his photographs, as if no rapid developments were taking place in the huge, modern docks. In 1882, that is before he took up photography, he wrote: ‘Yesterday I was briefly in Rotterdam. ... It is actually a beautiful city. Always bustling, dirty and picturesque. ... I couldn’t give two hoots for the new parts.’9

16

George Hendrik Breitner

The Damrak in Amsterdam with in the background the Victoria Hotel and Central Station

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 2255

17

George Hendrik Breitner

View on the construction site at the Van Diemenstraat in Amsterdam

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 2223

One of Breitner’s Rotterdam photographs gives us a striking example of how he ‘looked away’ from the contemporary renovations, urban development, modernisation and expansion that were transforming the city. This is the photograph he made of the Koningsbrug, the bridge which used to connect the old ramparts (the Bolwerk) with the Oude Hoofdplein, where horses and carts were always standing [18]. Two horses occupy almost the whole frame; in the background we can only just see the houses that used to stand on the Geldersekade, Mosseltrap and the Spaansekade: the area around the old harbour. The photograph must have been taken in or before 1905: that year the cast iron bridge railing, which is still visible on the photograph, was replaced.10

Breitner pointed his lens at the old city centre, with his back to the Nieuwe Maas river. If he had rotated through 90 degrees, then a completely different cityscape would have come into view. To discover what was behind Breitner, we need to consult a picture by the Dordrecht photographer Johann Georg Hameter [19]. Nearly 30 years earlier, in 1877, Hameter focused his camera on the railway bridge over the Nieuwe Maas, which had just been completed and formed an important link in the Amsterdam-Antwerp line. Before that the Amsterdam and Antwerp lines were not connected: one came to an end at the south side of the Maas, and the other to the north. A steamer had to carry passengers between the two banks of the river.

Hameter must have stood on the Oude Hoofdplein, on practically the same spot as Breitner: visible in the background to the right are the Bolwerk and the Boompjes waterfront. Behind the railway bridge we can see the foundations of the Willemsbrug which would be opened one year later in 1878, and which was intended for ‘normal’ traffic. In the course of his career Hameter photographed various bridges, viaducts, stations and docksides usually presenting them in a monumental way. These images celebrate the advanced feats of engineering that were accomplished in a push to improve the country’s infrastructure in the second half of the nineteenth century. Hameter’s photographs make no secret of the fact that new structures were rising up from the Dutch landscape, which were infinitely larger and more complex than those of previous centuries.

Breitner, on the other hand, firmly shuns the signs of progress. As with his pictures of Amsterdam, he ignores the monumental buildings that were going up in Rotterdam. Instead of ocean liners, he shows us river barges; in place of modern docks bustling with trade, we see traditional small businesses such as a hot-water shop, a rag-and-bone merchant and a blacksmith [20-21].

18

George Hendrik Breitner

Koningsbrug te Rotterdam

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 429

19

Johann Georg Hameter

Spoorbrug over de Maas bij Rotterdam, gezien vanaf het Oude Hoofdplein 1877

Lichtdruk 27 x 47,5 cm

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. nr. RP-F-F80014

20

George Hendrik Breitner

Gezicht op de Haringvliet te Rotterdam, 1906-1914

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 1306

21

George Hendrik Breitner

Hoefsmederij aan de Goudsesingel te Rotterdam

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 1342

Notes

1 For the troubled relationship between photography and art in the nineteenth century, see: Hans Rooseboom, ‘Myths and misconceptions: photography and painting in the nineteenth century’, in: Simiolus. Netherlands quarterly for the history of art 32 (2006) 4 [= 2008], pp. 291-313.

2 Tineke de Ruiter, ‘Foto’s als schetsboek en geheugensteun’, in Rieta Bergsma and Paul Hefting (eds.), George Hendrik Breitner 1857-1923. Schilderijen, tekeningen, foto’s, Bussum 1994, pp. 187-188: ‘Ik kan er niets aan doen wat Preyer gelieft te vertellen, vooral als [hij] ook nog waarheid spreekt. Buitendien ik gebruik wel degelijk photos Het is niet mogelijk dergelijke dingen te maken zonder hulp van photos. Hoe wil je dat ik een Amsterdamsche straat maak. Ik maak krabbeltjes in mijn schetsboek. als het kan een studie uit een raam. en een schets voor de details maar de keus. de compositie is toch van mij.’ (‘I can’t do anything about what Preyer [a colleague of the art dealer Van Wisselingh] wants to say, especially as what [he] says is actually true. And anyway, I do use photographs. It is impossible to make such things without the aid of photographs; how do you want me to portray an Amsterdam street? I make scribbles in my sketchbook, if possible, a study from a window and a more detailed sketch, but the selection, the composition, they are mine.’), p. 196.

3 For an overview of this genre in photography, see: Ingeborg Th. Leijerzapf, ‘Moment, Temperament and Athmosphere as Core Concepts 1889-1925’, in Flip Bool et al. (eds.), A Critical History of Photography in the Netherlands. Dutch Eyes, Zwolle 2007, pp. 102-145.

4 For different opinions on the relationship between Breitner’s paintings and photographs see: Paul Hefting, De foto’s van Breitner, The Hague 1989, p. 47; Tineke de Ruiter, ‘Foto’s als schetsboek en geheugensteun’, in Rieta Bergsma and Paul Hefting (eds.), George Hendrik Breitner 1857-1923. Schilderijen, tekeningen, foto’s, Bussum 1994, pp. 188, 191, 195; Tineke de Ruiter, ‘Tussen dynamiek en verstilling. Breitners glazen foto’s van Amsterdam’, in Anneke van Veen (ed.), G.H. Breitner. Fotograaf en schilder van het Amsterdamse stadsgezicht, Bussum 1997, p. 29; Rieta Bergsma, ‘George Hendrik Breitner: de schilder, zijn camera en zijn stad’, idem, p. 43.

5 That Breitner did not always achieve the desired effect in his exposures and thus needed to make adjustments afterwards can be inferred from his occasional use of chemicals to strengthen ‘thin’ or ‘soft’ negatives. (Anneke van Veen (ed.), G.H. Breitner. Fotograaf en schilder van het Amsterdamse stadsgezicht, Bussum/Amsterdam 1997, pp. 114, 125, 152, 171).

6 We should bear in mind that original negatives are only known from a modest number – about 20% – while many enlargements are printed with poor (greyish) contrast and many of Breitner’s negatives are ‘soft’ or ‘thin’, that is lacking in contrast, which could be remedied with chemicals. For this see Van Veen, pp. 114, 125, 152, 171, which notes Breitner’s methods of increasing contrast or improving definition. Cf. idem, p. 45.

7 Tineke de Ruiter, ‘Tussen dynamiek en verstilling. Breitners glazen foto’s van Amsterdam’, in Anneke van Veen (ed.), G.H. Breitner. Fotograaf en schilder van het Amsterdamse stadsgezicht, Bussum/Amsterdam 1997, pp. 17, 19. See also Rieta Bergsma, ‘George Hendrik Breitner: de schilder, zijn camera en zijn stad’, idem, p. 54.

8 Rieta Bergsma and Paul Hefting (eds.), George Hendrik Breitner, 1857-1923. Schilderijen, tekeningen, foto’s, Bussum 1994, p. 182: ‘leelijke, ziellooze doozen’.

9 Paul Hefting, G.H. Breitner. Brieven aan A.P. van Stolk, Utrecht 1970, p. 28: ‘Gisteren was ik nog even in Rotterdam. … ’t Is toch een mooi[e] stad. altijd woelig, smerig en schilderachtig. … voor ’t nieuwe gedeelte geef ik geen duit.’

10 Aad Gordijn, Paul van de Laar and Hans Rooseboom, Breitner in Rotterdam. Fotograaf van een verdwenen stad, Bussum 2001, pp. 33, 108 (cat. no. 73).