4. Pioneer of Street Photography

Although Breitner regularly took pictures in and around his house and studio (showing interiors, nudes, portraits and pets) these scenes form only a small proportion of his photographic output. The majority of his photographs were taken out in the streets, specifically those of his hometown Amsterdam. Other cities photographed by Breitner include Haarlem, Rotterdam, Utrecht, Antwerp, Brussels, London and Paris, but of these there are far fewer. Breitner was among the first photographers who chose the street as their subject and workplace. Unlike earlier photographers, he was not interested in the city only for the sake of its buildings, but also for the figures that peopled it. In Breitner’s photographs, the urban setting is sometimes no more than a backdrop for scenes of everyday life. Whereas other photographers kept their distance, he simply walked the streets with his camera, brushing shoulders with other pedestrians. This was then a revolutionary approach [1].

As a result the Amsterdam pictured by Breitner seems less static and desolate than that of photographers such as Pieter Oosterhuis and G.H. Heinen [2]. Breitner’s pictures are often filled with people walking, shopping and chatting and children playing together. Breitner differed from other photographers in that he took full advantage of the possibility offered by newer, smaller cameras to make snapshots. In Breitner’s time, the term ‘snapshot’ denoted a photograph taken quickly and without concern for a balanced composition in accordance with the ‘rules of art’.1 Photographs taken with such simple cameras could not compete technically with those made with bigger, more complex cameras in use until then (and which would continue to be standard for a long time to come). Breitner, no doubt, cared less about technical perfection than about the chance to move inconspicuously among his fellow citizens, not feeling hampered by the size and weight of his camera. No other Dutch photographer managed to capture the liveliness and activity witnessed in Breitner’s photographs. Internationally too, he can be ranked among the pioneers of street photography, a group for whom the capturing of an atmosphere or impression was ultimately more important than technical perfection. Breitner is one of a line of painter-photographers that includes Pierre Bonnard, Maurice Denis, Edvard Munch and Édouard Vuillard, all of whom specialised in producing informal, strikingly direct and unpolished photographs, their images cropped in unusual ways and taken from unconventional viewpoints.2 Possibly even closer in spirit to Breitner are the less well-known German draughtsman Heinrich Zille and the French painter Henri Rivière, whose technique and subject matter are closely related.3

1

George Hendrik Breitner

Gezicht op het Spui te Amsterdam

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 1166

2

G.H. Heinen

Prins Hendrikkade en St. Nicolaaskerk, gezien vanaf het Centraal Station, Amsterdam

Lichtdruk

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv.nr. RP-F-F25738-H

3

George Hendrik Breitner

Passante op de Prinsengracht te Amsterdam

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 115

4

George Hendrik Breitner

Dienstbode bij de Westermarkt te Amsterdam

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 126

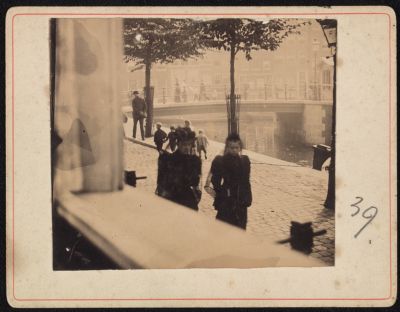

Breitner often photographed people walking across the picture frame. Some look into the camera, others are unaware of his presence. He particularly liked to position himself close to a bridge, presumably because relatively large numbers of people (as well as horses and carts) tended to converge there. On at least two occasions he took up a position at one corner of the Westermarkt to photograph a housemaid. In both pictures a woman is walking in exactly the same place and is just inside the frame – two seconds later and each would have stepped outside the range of the viewfinder; the rest of the square is nearly empty. The similarity is so striking that it is hard to believe Breitner did not deliberately choose to capture them in this way [3-4]. Another place where Breitner could observe his subjects freely was a merry-go-round on the Haarlemmerplein [5-6]. He also photographed pedestrians and activity in the street from a first-floor window of the artists’ society Arti et Amicitiae on the Rokin, as well as from his house on Lauriergracht [7-8]. Breitner enjoyed making photographs in series, or at least he often took more than one picture at a time. Good examples are the Haarlemmerplein photographs that feature a blacksmith and dancing children in a playground [9-10]. There were also places such as the Damrak and the junction of the Korte Prinsengracht and the Haarlemmerstraat, to which he regularly returned with his camera.4

5

George Hendrik Breitner

Kermis op het Haarlemmerplein te Amsterdam

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 588

6

George Hendrik Breitner

Kermis op het Haarlemmerplein te Amsterdam, 1900 c.

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 595

7

George Hendrik Breitner

View of the Lauriergracht in Amsterdam with pedestrians

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 2036

8

George Hendrik Breitner

View of the Lauriergracht with pedestrian

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 2041

9

George Hendrik Breitner

Kinderen in speeltuin het Vosje te Amsterdam, voor 1901

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 1291

10

George Hendrik Breitner

Kinderen in speeltuin het Vosje te Amsterdam, voor 1901

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 1292

Every so often Breitner would pause somewhere to photograph people as they were working or standing still. He regularly circled around his subject. Although the people he intended to photograph often had their backs towards him, he did not always go undetected. In fact, it is something he seems not to have been particularly bothered about: several photographs show that he placed himself directly in front of his subject. Sometimes we can see that he followed adults or children around for a time, and they would perhaps turn around briefly before walking on, apparently unperturbed by the camera [11-12].

Roughly 2850 negatives and prints are known to us and these were made using various cameras, some of which have been preserved. Among these is a simple box camera that took 9 x 12 cm glass negatives, and allowed him to take several pictures in quick succession, inconspicuously. Breitner probably bought this camera around 1900. 5 Worn patches and paint stains suggest that Breitner used the camera a great deal, and lends credibility to the notion that Breitner was still very productive as photographer after 1900. He must have owned a camera that took this size of negative in earlier years. One of the photographs matching this format was made between 1894 and 1898 and in it, to the right, we can see a man who is relieving himself [13].6 It looks as if he noticed the camera pointing at him while urinating: he glances sideways towards the camera. He must have been surprised that his picture was being taken, since photographers working in the street were an exceptional sight in those days, whether amateurs or professionals. Very few private individuals had a camera at that time: photography was a leisure pursuit that consumed more time and money than the average Amsterdammer could afford.

Because cameras were seen so rarely in the street at the time, there was every chance that people stopped what they were doing as soon as they realised that Breitner was photographing them, and that they turned towards him, staring into the lens and so spoiling the scene and composition that had attracted Breitner’s eye. We know both from photographs and stories told by others that children could be especially curious and would make a nuisance of themselves by standing in front of the camera [5].7 Sometimes people objected to being photographed, as in 1913 when the Amsterdam photographer Johan Huijsen visited the Jordaan area, the Zeedijk and the Jewish quarter, known as ‘dark Amsterdam’. He was told to push off to the more prosperous central canals rather than take advantage of people’s poverty.8

By 1913 photographers had probably become a common street phenomenon, and this means that Huijsen and others needed to take camouflaging measures, whereas Breitner had been photographing the city at a time when cameras were still so rare that they tended to go unnoticed. Nevertheless, at times it was important to act swiftly and without attracting attention and this helps to explain why Breitner preferred smaller, easy-to-use cameras. Several photographs taken with the sun behind reveal Breitner’s shadow in the foreground. From his pose we can tell that he was holding a small model at chest height, which he would have been able to operate fairly inconspicuously [14]. The negatives produced with this camera, measuring c. 6 x 9.5 cm, are among the smallest that have been preserved.9 He also used a bigger model that produced negatives of 13 x 18 cm. Too heavy to be hand held, this camera had to be mounted on a tripod and was mostly used for static views of the city with few or no people.10

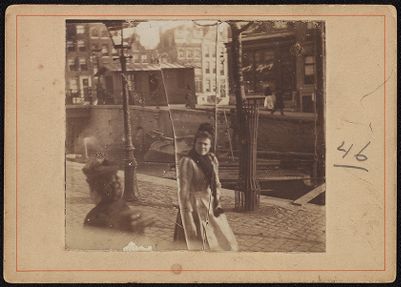

Although Breitner took his subject matter predominantly from the street, recording life as it hurried past, he occasionally engineered a composition. We see people posing in the street, at a building site but also in a garden (his?) [15-16]. There is one set of photographs that shows two girls (probably dressed up for the ‘Hartjesdag’ festival), gazing down in one photo and up into the camera in the other [17-18]. Another pair of photographs shows the same girl, probably Geesje Kwak, once in profile and once in frontal view [19-20]. In at least two cases Breitner was clearly trying to capture movement. In one of these studies we see a running woman and her shadow as well as the shadow of a second running woman, who is outside the frame [21-22]. The fact that Breitner used a fence to provide a neutral background adds to the impression that this is a study of motion: for the pose to be properly appreciated it was necessary for the figure to stand out as sharply as possible from the background. Breitner may have picked this up from the British photographer Eadweard Muybridge, who moved to the US and in the 1890s produced countless studies of movement using a wooden frame as backdrop [23]. 11

11

George Hendrik Breitner

Kinderen op de Galgenbrug richting de Bickersgracht te Amsterdam

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 1374

12

George Hendrik Breitner

Gezicht op de Galgenstraat met de brug naar de Kleine Bickerstraat

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 1373

13

George Hendrik Breitner

Oudezijds Achterburgwal, Amsterdam 1894-1898

Ontwikkelgelatinezilverdruk, 264 x 361 mm

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. nr. RP-F-00-621

14

George Hendrik Breitner

Gezicht op het Spui te Amsterdam

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 1118

15

George Hendrik Breitner

Construction site at the Van Diemenstraat in Amsterdam, 1889-1896

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 2052

16

George Hendrik Breitner

Cityscape with the portrait of a young girl

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 2025

17

George Hendrik Breitner

Portrait of two young girls at the "Hartjesday"

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 2263

18

George Hendrik Breitner

Portrait of two young girls at the "Hartjesday"

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 2032

19

George Hendrik Breitner

Portrait of Geesje Kwak in the snow

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 2034

20

George Hendrik Breitner

Portrait of Geesje Kwak in the snow

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 2035

21

George Hendrik Breitner

Portrait of a woman passing by, 1889-1915

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 2050

22

George Hendrik Breitner

Portrait of a woman passing by

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, inv./cat.nr. BR 2021

23

Edward Muybridge

View of the arrangements for measuring the strides and background

collodiumdruk

Plaat CVII in J.D.B. Stillman, The Horse in Motion, Boston 1882

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. nr. RP-F-F25737-C

Notes

1 See Gordon Baldwin and Martin Jürgens, Looking at Photographs. A guide to technical terms, Los Angeles 2009, p. 80, and Colin Harding, ‘Snapshot Photography’, in John Hannavy (ed.), Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography, New York/London 2008, p. 1279.

2 See for example Elvire Perego, ‘Intimate moments and secret gardens. The artist as amateur photographer’, in Michel Frizot (ed.), A New History of Photography, Cologne 1998, pp. 334-345, and Elizabeth W. Easton (ed.), Snapshot. Painters and Photography, Bonnard to Vuillard, New Haven/London 2011.

3 For photographs by Zille see Matthias Flüge (introd.), Heinrich Zille. Berlin um die Jahrhundertwende. Photographien, München 1993; for those of Rivière: François Fossier, Françoise Heilbrun and Philippe Néagu, Henri Rivière, graveur et photographe, Paris 1988.

4 Anneke van Veen (ed.), G.H. Breitner. Fotograaf en schilder van het Amsterdamse stadsgezicht, Bussum 1997, pp. 150, 166-169.

5 Breitner’s 9 x12 camera is virtually identical to the ‘1901/1902 Model’ of the ‘Guy’s Edison-Camera’ reproduced in a catalogue of the renowned photographic supplier Guy de Coral. Breitner’s model was probably manufactured slightly before or after. For the camera, see for example: Paul Hefting, ‘Notities over G.H. Breitner’, in Bulletin van het Rijksmuseum 16 (1968), pp. 170, 172, Tineke de Ruiter, ‘Foto’s als schetsboek en geheugensteun’, in: Rieta Bergsma and Paul Hefting (eds.), George Hendrik Breitner 1857-1923. Schilderijen, tekeningen, foto’s, Bussum 1994, pp. 190, 198 (note 25) and Tineke de Ruiter, ‘Het fotografisch ambacht’, in Anneke van Veen (ed.), G.H. Breitner. Fotograaf en schilder van het Amsterdamse stadsgezicht, Bussum/Amsterdam 1997, p. 111.

6 Anneke van Veen (ed.), G.H. Breitner. Fotograaf en schilder van het Amsterdamse stadsgezicht, Bussum 1997, pp. 77, 139 (cat. no. 55).

7 Hans Rooseboom, ‘Eenvoud als antidotum. Vier foto’s van A.J.M. Mulder’, in: Bulletin van het Rijksmuseum 56 (2008), pp.154 (fig. 3), 155 (fig. 4), 157; Hans Rooseboom, De schaduw van de fotograaf. Positie en status van een nieuw beroep, 1839-1889, Leiden 2008, pp. 160-162.

8 J. Huijsen, ‘Fototochten in donkerst Amsterdam’, in De Camera 5 (1912-1913), pp. 157, 163.

9 Tineke de Ruiter, ‘Foto’s als schetsboek en geheugensteun’, in Rieta Bergsma and Paul Hefting (eds.), George Hendrik Breitner 1857-1923. Schilderijen, tekeningen, foto’s, Bussum 1994, p. 198 note 22.

10 Tineke de Ruiter, ‘Tussen dynamiek en verstilling. Breitners glazen foto’s van Amsterdam’, in Anneke van Veen (ed.), G.H. Breitner. Fotograaf en schilder van het Amsterdamse stadsgezicht, Bussum 1997, pp. 17-19, and Anneke van Veen, ‘Het raadsel van Breitners glasplaten’, idem, p. 122.

11 See also Tineke de Ruiter, ‘Foto’s als schetsboek en geheugensteun’, in Rieta Bergsma and Paul Hefting (eds.), George Hendrik Breitner 1857-1923. Schilderijen, tekeningen, foto’s, Bussum 1994, p. 189, where the author makes a connection between Muybridge and Breitner’s paintings, but does not mention this study of motion by the latter.